European and Czech defence industry at a crossroads

Since the 2014 summit in Wales, which took place after the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the start of the conflict in Ukraine with the creation of two Russian-backed "people's republics" of Luhansk and Donetsk, every subsequent summit has repeated Washington's public appeal to its European allies: defence spending needs to be raised to two per cent of GDP. At the same time, less publicly, the Americans have added that higher arms spending should be used mainly to buy US weapons. Given American interests and the strength of its military-industrial complex, this was logical. This pressure intensified after the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

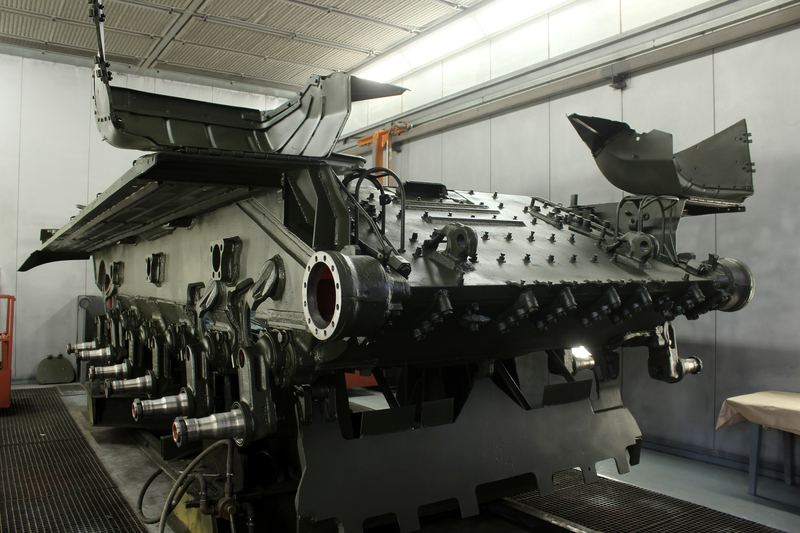

Picture: In the context of the Ukrainian conflict, there is increasing talk of the need to develop the capabilities of the European, and hence Czech, arms industry and to increase its production. (illustration photo) | Shutterstock

Picture: In the context of the Ukrainian conflict, there is increasing talk of the need to develop the capabilities of the European, and hence Czech, arms industry and to increase its production. (illustration photo) | Shutterstock

The truth is, however, that American pressure (made especially famous by former US President Donald Trump – just remember the 2018 NATO summit in Brussels) has produced results. Although most EU members have not yet passed the two per cent of GDP bar, defence spending has risen steadily across Europe in the eight years following Wales. In 2022, the total was up 13 per cent, reaching $345 billion, a third more than a decade ago. Russia's war in Ukraine has undoubtedly been a major impetus for European arms spending to increase. They now exceed the amount spent on defence by China and Russia combined.

However, the question of whether Europe's arms needs can be better met by European arms production is coming to the fore. At the international Globsec conference in Bratislava, French President Emmanuel Macron, a great advocate of European strategic autonomy, said the following words: "We need to create a truly European military-technological and industrial base in all the countries involved and deploy truly European equipment at European level".

This is an ambitious goal, but one that is being challenged by political, military and economic realities. The US cannot, of course, be interested in seeing those European countries that spend around half their military budget on buying US weapons change their policy in any major way. While some European countries are planning for this to happen, it still faces considerable limits. Indeed, the arms industry across Europe has been forced to collect a 'peace dividend' in the years since the end of the Cold War and has therefore not developed much, but rather stunted. And even though today it receives many times more resources than before, it is not possible to radically expand or modernise production overnight, or even to launch a completely new production. This is illustrated, for example, by the production of Leopard 2 tanks, where the manufacturer of these tanks, KMW, is capable of producing a complete tank, but its production rate was until recently 'snail-like': several Leopards a month were coming out of the factory gates.

In May this year, Thierry Breton, the European Commissioner for the Internal Market, said that the plan was to use EU money directly to support efforts to build a European defence industry, which is important for both Ukraine and European security. Indeed, billions of euros have begun to flow into it, including from the European Defence Fund. However, achieving the stated goal of greater independence from the United States may be a very long haul. Moreover, it may also be affected by the fact that the defence industry is considered by many banks and investment companies to be 'non-green' and therefore unviable, which limits its lending opportunities. While the European Commission has attempted to correct this view (including in its 19.12.2022 Communication on the interpretation of what exactly the taxonomy means), the Commission's position may not be determinative for banks and investment companies.

At the same time, it is interesting to note that even the US arms industry, despite its scale, may not be able to make up the shortfall in arms supply, as the war in Ukraine has confirmed. For example, the largest US ally in Europe, Poland, has established extensive cooperation with South Korea, which is expected to result in the licensing of specific Polish versions of self-propelled howitzers, tanks and aircraft. At the same time, the South Koreans have both spare production capacity and the ability to expand it to Polish territory. This may be a repeat of the success story of the penetration of the European market by Korean carmakers. The question, of course, is whether the Polish state budget is capable of financing such large-scale arms production. Let us recall, however, the categorical slogan of Poland's most powerful politician, the chairman of the Law and Justice party, Jarosław Kaczyński, that 'it is better to be indebted than occupied...'.

Undoubtedly, from the above description of the current situation on the European defence industry "front", a few conclusions can also be drawn for the Czech Republic, where the robustness and capabilities of the domestic defence industry not only significantly strengthen its defence capability, but also contribute to economic and social development and employment. The key companies of the Czech defence industry demonstrate this. At a time of widespread austerity, this is a very crucial and perhaps as yet unappreciated issue, where it is logical that the state's comprehensive and continuous support for defence industry enterprises should be reflected in a well-thought-out acquisition policy. It is one thing to declare support for arming the army with new weapons systems, but it is another thing to see how this is implemented in practice. The slowdown in the acquisition process was most recently signalled by the State's Chapter 307 accounts for last year. Let us also recall that the new Czech security strategy adopted by the government this year makes no mention of the role of the defence industry in the country's defence.